Índice

ToggleThe drought of 2023 in the Amazon is still a story to be told. Rarely has the force of nature been so relentless, even in an environment already accustomed to the extremes of its natural cycles. Every year, the Amazonian knows that the waters will rise and fall. And they have learned to adapt themselves to this reality. But last year, the climatic effects surpassed all limits. The rivers did more than dry up: some disappeared. Animals lost their refuges, and thousands of them died. In Lake Tefé, Amazonas state, researchers from the Mamirauá Institute had to collect 222 carcasses of tucuxi and pink river dolphins over two months. Why did this unprecedented mortality of aquatic mammals occur? And what warning does it bring about the climate crisis? Amazônia Real reconstructs this sad episode step by step, listening to experts and people who were involved in the vain attempt to save the animals.

Tefé (Amazonas state) – It was supposed to be a day-off on a Saturday for biologist Mariana Lobato and researchers from the Mamirauá Institute, located at Lake Tefé in Amazonas state. Most of the Amazonian Aquatic Mammals Research Group, composed mostly of women, had just returned from the Amanã Sustainable Development Reserve (RDSA), where they had gone to conduct animal health analyses. But an unexpected phone call on the afternoon of September 23, 2023, startled everyone — and canceled their well-deserved rest.

The initial reports indicated that about 17 pink river dolphins and tucuxis were found dead in Lake Tefé. Mariana couldn’t believe what she was hearing until she went down to the river and saw the bodies of the animals floating. “What is happening?” was the most frequently asked question in the following days. Like the local residents, the researcher also had no explanations.

There were no reports, records, or research on pink river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) and tucuxi dolphins (Sotalia fluviatilis), two species of freshwater dolphins living in Lake Tefé. The academic platforms that store scientific knowledge offered no clues. Researchers particularly examined studies and records from 2010, the year of the last extreme drought. But there was nothing that correlated the appearance of aquatic mammal carcasses with elevated water and air temperatures. No specific line of this fatal story had been written before. The scene witnessed by Mariana Lobato was just the first sign that something much more grave was about to unfold.

The pink river dolphin and the tucuxi are highly symbolic for the Amazonian people. They are part of their culture and stories. “We didn’t see any signs of human action, no harpoon marks, nets, or cuts. They were animals that appeared healthy on the outside,” recalls the biologist.

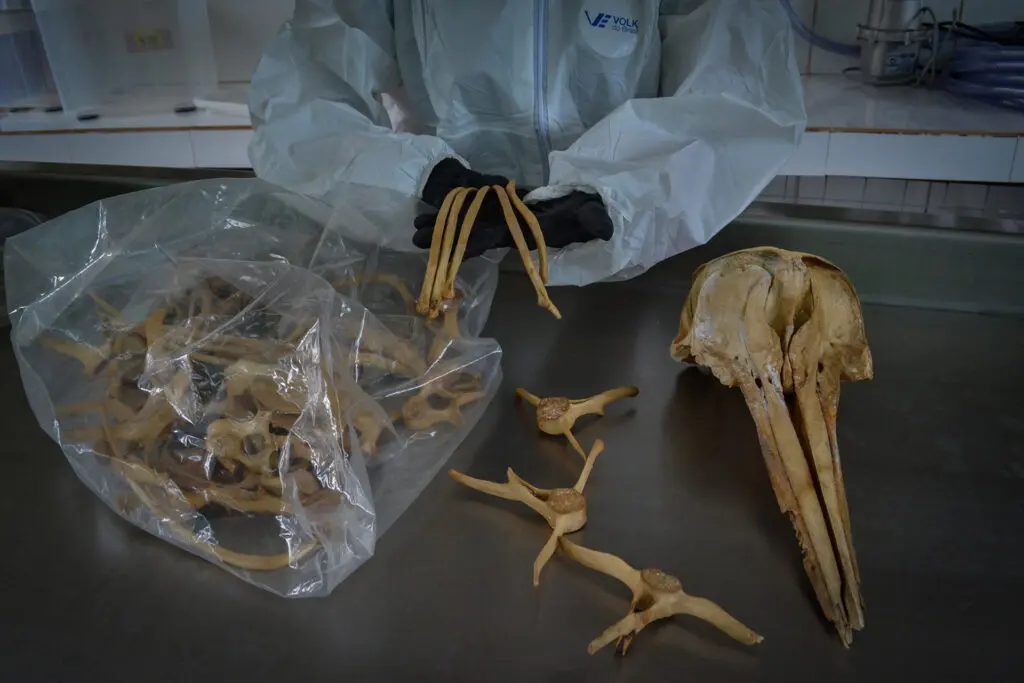

On September 27, a Wednesday, the Mamirauá team identified 28 more carcasses. It was the most tragic day. All institute collaborators, regardless of their research area, were mobilized to help with the collections. There were so many animal bodies that many could not be collected in their entirety. The researchers only cut off the skulls, the essential part for gathering the main information about each individual and conducting future analyses.

The female researchers had to fight against tiredness. Their workday began at 5 a.m. and ended at 11 p.m., inside the necropsy lab. They had to set up a camp at Lake Tefé, and even a boat served as a base on the lake. The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) established an emergency command at the site. At this point, the news had spread worldwide.

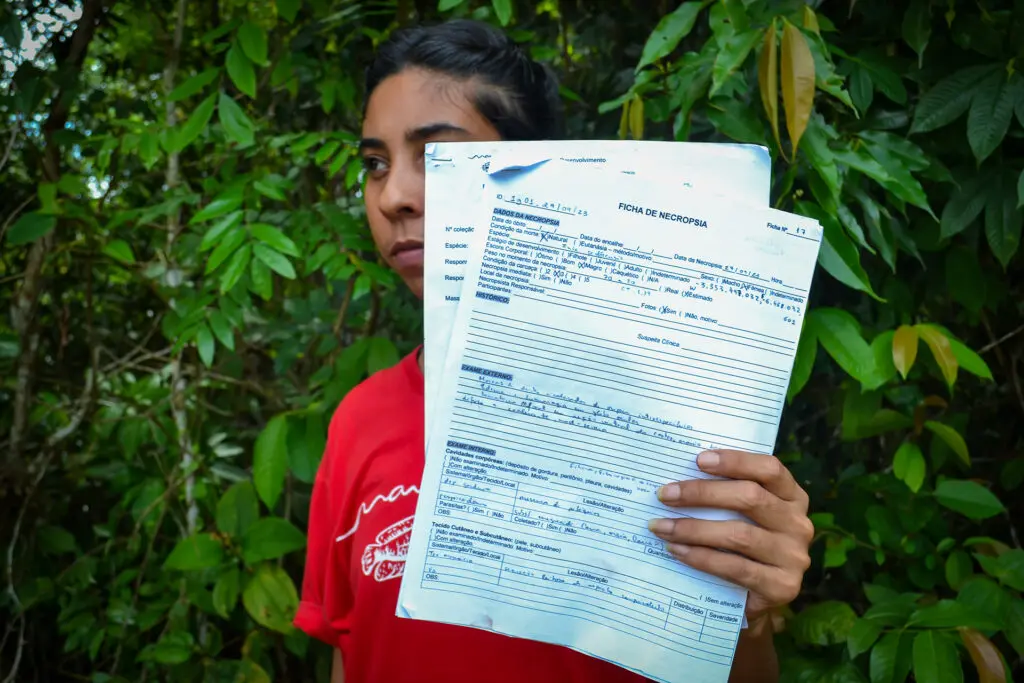

To find out whether what was happening was something chronic or acute, Adria Moreira, the veterinarian responsible for the necropsy, could not overlook any detail of her observations. An initial card was created from every piece of information that seemed relevant. The team only managed to set up a format for this document about 20 days after starting their work.

“Dealing with death itself was quite traumatic. I felt like I was in a war camp,” recounts Adria Moreira. Generally, professionals who perform necropsies are very technical: everything follows a protocol, with notes and image records, step by step. But this time, the scenes were shocking. “Even before entering, it was a huge blow, one that I never wanted to deal with death like this. But it was necessary.”

The level of decomposition of the bodies was “COD 4”, one of the most advanced, according to forensic medicine. At this stage, the analysis process is more complicated, and the researchers couldn’t infer much. For the veterinarian, it was psychologically difficult to face something never seen before and that required a lot of physical and mental effort, enlarged by the need to wake up early and sleep very late in those days. “It was something that happened emergently, there was no way to avoid it or choose,” she says.

Initial investigations

Bacteria, virus, or extreme heat? Faced with an unprecedented climate crisis in the Amazon, the latter hypothesis seemed to carry more weight. For the researchers, the heat could be exacerbating a picture of pulmonary or cardiac disease generally found in cetaceans (aquatic mammals). The warmed water could contribute to the proliferation of a bacterial or infectious disease that might already be present in the animals.

The researchers considered moving the animals from the lake, which was very dry, to the main river. Many outsiders were calling for urgent measures. However, this option would entail the risk of spreading a disease, if there was one, to the rest of the Amazon River. This doubt dissipated when the results of the bacteriological tests came back negative, reinforcing the hypothesis of the deadly effect of the heatwave. In those months, the Amazon region exceeded 40°C, and the drought in the Rio Negro [which forms the Amazon River along with the Solimões] had already reached its lowest level in 119 years: 13.59 meters.

According to a report from the National Center for Monitoring and Alerts of Natural Disasters (Cemaden), with data from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2023 was the hottest year since global records began in 1850. The largest anomalies were recorded from September to December 2023, with temperatures 4 to 5 degrees above average. According to the National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet), there were 6 intense heat waves between August and November 2023.

The external heat alone would already be an extreme situation, but there was another element to be considered that was visible to everyone. Mariana Lobato does not dismiss the contribution of the region’s wildfires, which were breaking records and left the capital of Amazonas state, Manaus, under smoke for months. “The air quality was terrible, and since fresh water dolphins are mammals, they don’t breathe oxygen from the water,” she explains. “They breathe atmospheric oxygen, and since they already have respiratory problems, this could indeed have contributed to respiratory issues,” she emphasizes.

Only after confirming that there was no contagious disease, the animals were released at the mouth of Lake Tefé, in an attempt to save the survivors.

Unexpected discovery

Without the presence of diseases in the examinations of the aquatic mammals, the research team collected water samples and conducted tests for biotoxins in search of microalgae and cyanobacteria (bacteria that obtain energy from sunlight). What they did not expect was to find a species of microalgae called Euglena sanguinea, which had never been recorded in the rivers of the Amazon.

“Euglena sanguinea produces a substance called euglenophycin, which is highly toxic to fishes. However, there are no studies on aquatic mammals,” affirms Mariana. The fish died days after the first river dolphins, which raises doubts as to whether the toxin contributed to the mortality, even if indirectly.

In two out of six samples analyzed from the tucuxi dolphins (Sotalia fluviatilis), a small amount of “palytoxin and analogues” was found, substances that are still a mystery to science. According to studies conducted by the research team at the Mamirauá Institute, palytoxin and analogues are causes of Haff disease, better known as “black urine”.

Cases of “black urine” have recently been reported by the Ministry of Health in Tefé. The symptoms of the disease caused by the ingestion of fish contaminated with the palytoxin molecule are muscle pain, headache and fever, which can be confused with flu, malaria or dengue fever, endemic diseases in the Amazon region.

Mariana Lobato believes that lack of access to healthcare in more remote communities and symptoms that can be confused with other diseases likely led to underreporting of cases in Tefé. In science, “palytoxin and analogues” are poorly studied. It is not known, for example, who or how they are produced and what their possible forms are. There are hundreds of analogous toxins already mapped, but how they are processed within the body remains unexplained. “So much so that the treatment for this disease (“black urine”) in humans is hydration. The person simply hydrates themselves and takes care of this disease,” she explains.

Scientific studies indicate that palytoxin and its analogues have caused diseases in marine mammals. However, pink river and tucuxi dolphins live exclusively in freshwater environments. This is a possible research avenue to decipher the massive death of animals in Lake Tefé. “This [palytoxin] in microdoses can cause muscle fiber breakdown, muscle pain, and justify the strange behavior they were exhibiting in the lake. It also causes brain failure and, most importantly, renal failure. This renal failure will cause the death of the animal,” adds the researcher.

“40 degrees Celsius bathtub”

In addition to palytoxin, its analogs and the species Euglena sanguinea, no metals, contaminants, or abnormal biotoxins were found in the water analyses. With poor air quality and severe drought, the researchers returned to the most concrete hypothesis of intense heat as the generator of a true environmental collapse.

“We even thought they [pink river and tucuxi dolphins] were trying to get out of the water, which was boiling, 40 degrees Celsius inside the water. Imagine yourself in a bathtub at 40 degrees Celsius wanting to get out, and then the air above was all full of smoke, terrible, how do you breathe? So you start to have extreme reactions,” says Mariana Lobato, who works as a laboratory technician.

The expected normal behavior for those who work and live with tucuxis and pink river dolphins is to observe the animals with shallow breathing every minute, foraging, and even playing. But that wasn’t quite what people and researchers observed. The behaviors deviated from normality. “They were animals thrashing in the water, jumping out of the water, literally struggling as if they were a dying fish. It was desperate,” adds Mariana.

The data increasingly support the hypothesis that the animals died due to heat, with temperatures reaching more than 10 degrees above normal. “Every necropsy we performed showed signs of thermal stress, extensive hemorrhaging, organ failure, the entire brain covered with blood marks, coagulated blood,” concludes the technician.

Ayan Fleischmann, coordinator of the Research Group in Geosciences and Environmental Dynamics in the Amazon at the Mamirauá Institute, states that high temperature is a key parameter for understanding the impact of droughts. In Lake Tefé, researchers measured temperatures that reached 41 degrees Celsius in the water column for several days, always in the mid-afternoon, a completely disproportionate value. “Outside of reality, when the average temperature normally ranges between 29 and 31 degrees Celsius,” the researcher compares.

Environmental stress

Zoologist Cláudia Souza monitors the carcasses on Lake Tefé; once a day the researchers at Mamirauá Institute monitors the water. Ádria Costa shows the necropsy technical sheet (Photos: Stéffane Azevedo/Amazônia Real).

On the necropsy side, veterinarian Adria Moreira and her team advanced in their analyses. What they notably observed were characteristics of a “hyperacute” environmental stress factor, with a lot of congestion and hemorrhaging. It is as if the bodies of the aquatic mammals were unable to react to the rising water temperatures. “The animal’s nervous system began to release substances, in this case, stress proteins, into the blood, and the vessels began to experience a very significant hemodynamic disturbance,” she says. Under normal conditions, there is a hemostatic balance between blood circulation and substances that flow outside the vessels. In Tefé, there was an extravasation due to this environmental imbalance.

The extravasation of stress substances is what caused hemorrhaging, congestion, and even circulatory shocks that led to the death of the observed animals, according to Moreira. The organisms of the pink river and tucuxi dolphins became disoriented due to the lack of osmotic equilibrium (movement of fluids in the organism) and static.

According to the specialist, in a shock like the one described, there is significant hemorrhaging in the cranial region as well as in the chest. Blood extravasates, forming clots and cerebral and pulmonary edemas, as well as causing pulmonary hemorrhage. In the kidneys, muscle protein begins to extravasate, intoxicating these organs. Adria also reports that the animals’ urine was bloody, indicating renal hemorrhage, a characteristic of shock in the organism.

“Rhabdomyolysis is a muscular stress that leads to renal hemorrhage. When you check it out, the urine is dark. I can’t say for sure that it’s rhabdomyolysis, but traces have been found in toxicology,” says the veterinarian. “It is known to occur in situations of very high stress, whether in fish or humans,” says Adria Moreira. “It’s a warning sign for us to stay vigilant, the rivers and the animals are suffering greatly from this environmental stress,” she warns.

Ecological collapse

Monitoring ruler at the level of Lake Tefé done by researchers at Mamirauá Institute during the 2023 drought (Photos: Stéffane Azevedo/Amazônia Real).

Having studied aquatic life in the Amazon for 40 years, ichthyologist Jansen Zuanon is a living witness to the devastating impacts of extreme droughts. With each severe event, underwater life finds itself in a battle for survival. As water temperature increases, the amount of available oxygen decreases, directly affecting the physiology of fish. These species, like humans and other vertebrates, have a thermal tolerance limit of around 40 degrees Celsius. Beyond this, the body’s proteins denature and cease to function.

“Proteins have a three-dimensional physical structure, with atoms bonded to each other by different types of forces. When it gets very hot, the atoms start to shake themselves, all these bonds are broken, and the physical structure of the protein disintegrates,” he explains. In Lake Tefé, the combination of high temperature and poor water quality resulted in the death of thousands of fish.

“These fish decompose, and the bacteria end up consuming more oxygen, which worsens the situation even further. This results in water conditions that are terrible not only for the fish themselves but also for aquatic mammals, as we saw in the case of the pink river and tucuxi dolphins,” says Zuanon.

Although some fish species have the “aiú”, an adaptation mechanism that inflames the lower lips to capture oxygen at the surface, tolerance to temperature varies. Different species succumb at different times, until the ecosystem collapse becomes inevitable. “It’s a domino effect,” says Zuanon. “The more fish die, the worse the water quality becomes, until it becomes unbearable for most organisms.”

In the floodplain, low oxygen levels are common during the dry season due to decomposing material. Some species have already adapted to this new reality of oxygen scarcity. They can withstand these conditions for up to two or three months, as it was the case with Lake Tefé.

Dry forest

The real impact of the extreme drought of 2023 on the igapó and floodplain regions is still uncertain, but previous studies and expert analysis provide worrying clues. Flávia Costa, a researcher at the National Institute of Amazonian Research (Inpa) in the area of Forest and Functional Ecology, explains that plants take time to respond to climate changes but have already shown sensitivity of the flooded forests, especially in the igapós.

“The issue with igapós is that they accumulate a dense layer of leaves on the ground, prone to fire,” says the researcher. This vulnerability is compounded by the record-breaking wildfires in the Amazon in 2023, with a 463% increase compared to 2022, according to the Fire Monitor of MapBiomas. In total, 1.3 million hectares were burned last year.

In the solid ground forests, droughts and high temperatures stress the vegetation, leading to a reduction in the capacity to store carbon or even to its loss, explains Costa. It works like this: plants close their stomata to prevent water loss but cease to absorb carbon for photosynthesis. Furthermore, the specialist continues, “extreme droughts increase mortality, reducing the number of trees that absorb carbon. The dead trees then begin to emit carbon into the atmosphere during decomposition.”

Joice Ferreira, an ecologist at Embrapa Eastern Amazon and co-founder of the Sustainable Amazon Network (RAS), explains that high temperatures exceed the tolerance limits of plants and animals, affecting their essential processes. According to Joice, the effects of different stresses end up accumulating and exacerbating the scenario even further.

For years, researching at RAS the long-term effects of external action impacts on the forest, she gives examples of what is already happening with dung beetles, which decreased in quantity and diversity after the 2015 drought, impacting seed dispersal and soil turnover in forests.

“The example of this group shows that everything in the forest is interconnected and that the loss of a group of flora or fauna functions like a chain reaction. These small insects are linked to many forest mammals, as they use their excrement as nests and food. Thus, their reduction also relates to the loss of larger mammals,” she concludes.

Environmental condition in Manaus

Manaus had never experienced such intense smoke from wildfires before. It was months under the toxic air that left clothes smelling of burnt material and created a thick haze that lasted for days, causing health issues. But, by geographical luck, the capital of Amazonas and a larger region to the northwest, within the Guiana Shield, have an environmental condition that can alleviate the problems of heat and drought on the solid ground forest, says Flávia Costa.

“In this region, the soils tend to be deep and clayey, which retains a lot of water from rainfall, which then slowly replenishes the streams through groundwater migration,” says the researcher. Thus, a large water stock is formed in the soil and the water table that can “save” the forests, as long as the rainy periods continue to be able to infiltrate this reservoir. “We have observed greater resilience of our forests compared to other regions of the Amazon. This does not mean that the forests here do not suffer, only that they suffer much less than regions like the southern and southeastern portion of the Amazon,” she reports.

This equation only adds up, crystal clear, if the forests in the region are not degraded. According to the researcher, forests will remain viable where they are large and not isolated, as small areas may lose sensitive species. “We have seen a much more negative response from the vegetation, as well as from the animals, to the 2023 drought in the forest fragment on the Ufam (Federal University of Amazonas) campus. Since this area is relatively small and surrounded by the city, the intense heat and the deficit of moisture in the air cause significant stress on the vegetation,” says Flávia Costa. An evident sign was the plants that became quite wilted, as the researcher herself witnessed during one of her walks.

Savannization of the Amazon?

In this cycle of repeated and intensifying droughts, with increasing vegetation fires, it is expected that the forest will change its “appearance”. It is not difficult to comprehend the reason why. The ecologist Joice Ferreira describes that some taller tree species, especially those that reach the forest canopy, are more vulnerable to the stresses of drought and tend to die off more. In the medium to long term, the dense vegetation becomes lower. On the other hand, other species are more adapted to degraded environments, such as bamboo, vines, and certain palms like the babassu palm. However, the proliferation of these more adapted species tends to reduce the diversity of other species that were adapted to more preserved and humid environments.

“After many drought and wildfires, we expect a forest with a drier, sparser, lower, and less diverse appearance, with species more tolerant to these stresses. Regarding animals, we observe a reduction in diversity, which ends up favoring those more generalist species that adapt to disturbed environments,” comments Joice Ferreira. Researchers have already observed and are now quantifying the extent of this adaptive struggle. Rare or larger bird species, for example, tend to disappear, and in their place, smaller and more common species related to plants with smaller seeds gain more space.

The transition of the Amazon as we know it may still be of a forest, but with different and less humid characteristics. According to the researcher from Embrapa Eastern Amazon, areas affected by drought and fire have become more simplified and impoverished. After the fire, there is a change in the quality of the forest which includes sparser, more open vegetation, with a reduction in species, dominance of more generalist species, and plants with less carbon

“Today there is much talk about savannization. However, savannas typically have a layer of grasses and another of trees, and they can be very rich and diverse, as is the case with the Brazilian cerrado. So far, we do not have evidence for these wet areas we study of a shift towards savannas,” she emphasizes.

Uncertain future

What lies ahead? This question resonates among scientists and the local population regarding the phenomena and responses the Amazon provides to the climate crisis. “I don’t have good prospects. But we don’t know what will happen with this global warming issue. Just as we had a very severe drought, we might have an even worse flood, and we never know the consequences of these droughts and floods because it’s all very new,” laments Mariana Lobato.

At the Mamirauá Institute, the historic drought of 2023 forced researchers to realign their work plans from now on. What can be done to prevent mortality levels like those of the pink river and tucuxi dolphins from repeating in the future? “We noticed a drastic reduction in the number of animals in Lake Tefé. There is a very high chance that if something like this happens every year, [the species] will disappear because it was very extreme,” projects Mariana.

In the end, researchers at the Mamirauá Institute counted the deaths of 222 pink river and tucuxi dolphins in Lake Tefé. In Coari, another municipality in Amazonas, there were 121 animal deaths, although some showed signs of human interference. In the literature, there were records of deaths only in salt water dolphins associated with hyperthermia and diseases, a reality apart from those found in the Amazon this time.

One of Mariana Lobato’s nuisances was having to send samples to other states in the South of the country to get test results. She mentioned that while the team received significant support from other institutes and research groups, the lack of necessary investment in the Amazon to respond to crises like the one in Lake Tefé is problematic. As of December, the researchers were still waiting for some of the test results and continue to wait four months after the event.

“You know what I truly felt? There was a lot of partnership, really a lot. That was great, but we still face significant difficulties in conducting analyses here in the Amazon. We always have to export everything, you know? It has to go to the Southeast, it has to go to the South. It has to go somewhere else. Why can’t we do things here?” she questions.

El Niño in 2024?

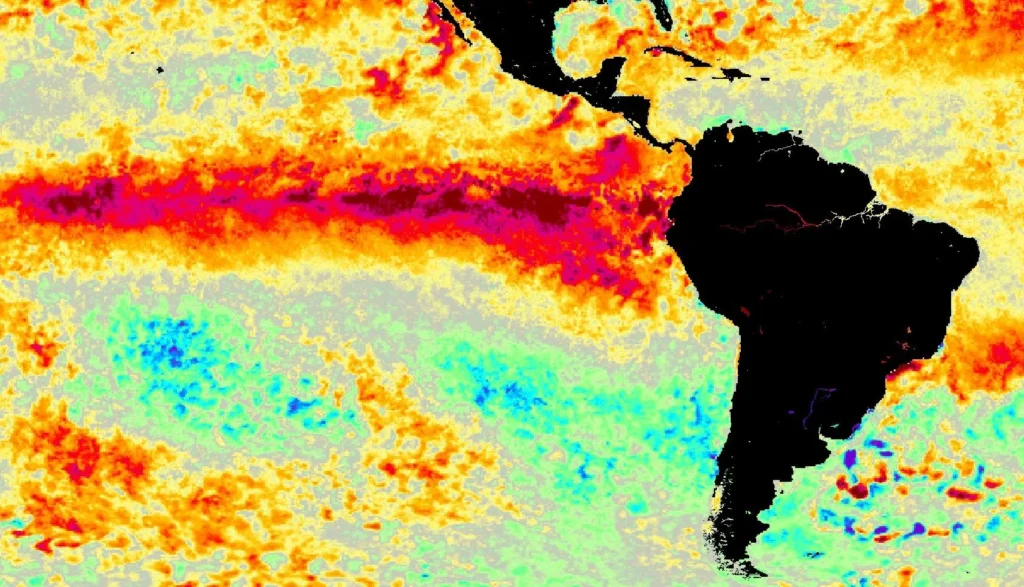

Ayan Fleischmann’s analyses confirm that the temperature recorded during the historic drought of 2023 is linked to the climate crisis, exacerbated by El Niño and the warming of the North Tropical Atlantic Ocean. This combination of factors led to reduced rainfall and a prolonged dry period in the Amazon region, resulting in increased solar radiation and lower water levels. In other words, El Niño could last for another two years.

“All these events raise a huge alarm. Next year, if El Niño persists and the North Tropical Atlantic Ocean remains warm as is a concrete possibility, we could again experience a severe and extreme drought in September and October of 2024,” affirms Fleischmann.

According to the researcher, the management of the climate crisis and environmental disasters in Brazil come up from a lack of preparation by the authorities. It is vital to review actions aimed at minimizing socio-environmental impacts. With the recurring flood and drought periods, which vary in intensity each year, the researcher believes that the Amazon faces two potential disasters annually. To address them, it is necessary to plan not just months before the peak of each phenomenon. “We cannot wait for the flood to pass to start thinking about the drought. We need to work on the prevention of all disasters, adapting ourselves to these disasters and the climate crisis in a permanent and urgent manner,” he advises.

* The original version of this article is in Portuguese and can be accessed here

To ensure the protection of press freedom and freedom of expression, Amazônia Real, an independent investigative journalism agency, does not accept any form of public funding. This includes funds from individuals or companies associated with environmental crimes, slave labor, human rights violations, or violence against women. This commitment to coherence is of utmost importance to us. As a result, reader donations play a vital role in enabling us to produce more in-depth reports on the Amazon’s reality. We sincerely appreciate the support of all our readers. If you would like to contribute, please consider donating here.

As informações apresentadas neste post foram reproduzidas do Site Amazônia Real e são de total responsabilidade do autor.

Ver post do Autor